Here’s How New York City Will Split Ventilators to Treat Covid-19

New York City is preparing for the worst and hospitals are exploring options to support more patients in critical condition than they’ve ever had to handle before. One option that is getting a lot of press is the idea of ventilator sharing, or configuring one machine to handle two or more patients simultaneously by splitting it.

This is what we are down to. Splitting ventilators, and facing serious dilemmas like choosing who will be actually ventilated when everybody should. , bloody seriously.Never thought it was so bad. Thx to for the inspiration and tips.

— marco garrone (@drmarcogarrone)

“We’re doing something that hasn’t really ever been done before,” Dr. Jeremy Beitler, a pulmonary disease specialist at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia the New York Times. “Now is the time to do it.”

New York State has approved the new method for dual-patient support on a single ventilator, while the FDA has granted approval to use a device named VESPer, which can support up to four patients simultaneously.

Why Can’t Everybody Share?

Here’s the problem with attempting to split one ventilator between patients: Because the machine isn’t designed for this method of function, the modifications debuted to-date use valve splitters and T-tubing to connect 2-4 patients to the same system. But ventilators do not simply push air in and out — they are carefully calibrated to the needs of the specific individual and their medical situation. Air pressure settings may be different for each individual patient in a way the ventilator can’t properly support. Furthermore, there’s a risk that a pathogen living in one patient’s lungs could contaminate the system and be inhaled by other patients. All mechanical equipment is subject to failure risk, including ventilators, and if every ventilator is hooked up to 2-4 people, a single point of failure now risks killing 2-4x more people.

In an ordinary situation, we would assume that this risk could be mitigated by deploying another ventilator. But we’re heading into a crisis in which literally every ventilator is expected to be spoken for. Equipment failure won’t just mean a bad few minutes; it could kill all of the people attached to the system. As this isn’t a normal situation, we need to explore every option to mitigate the disaster that’s hitting the New York City hospital system and possibly points beyond in the near future. America is now the epicenter of the world epidemic.

An estimated additional 87,000 hospital beds and 40,000 ICU beds are estimated to be necessary to deal with increased coronavirus demand in NYS alone. To date, 138,376 people have been tested state-wide, with 44,635 cases active in NYS. (By the time you read this, the numbers will probably have changed, but I’m pulling data from Worldometers.)

Not Everyone Agrees With New Measures

There are real concerns that attempting to split ventilators will result in 2-4 patients receiving subpar therapy rather than one person receiving a life-saving machine. The American Association of Anesthesiologists opposes ventilator sharing, :

The physiology of patients with COVID‐19‐onset acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is complex. Even in ideal circumstances, ventilating a single patient with ARDS and nonhomogenous lung disease is difficult and is associated with a 40%‐60% mortality rate. Attempting to ventilate multiple patients with COVID‐19, given the issues described here, could lead to poor outcomes and high mortality rates for all patients cohorted. In accordance with the exceedingly difficult, but not uncommon, triage decisions often made in medical crises, it is better to purpose the ventilator to the patient most likely to benefit than fail to prevent, or even cause, the demise of multiple patients.

The ASA writes that ventilator sharing should not be implemented “while any clinically proven, safe, and reliable therapy remains available.”

Whether you believe Covid-19 is a serious threat to you or not, take a moment to consider the astounding nature of that paragraph. These are the decisions doctors are forced to make when operating in conditions that we, fortunately, have all but banished from our day-to-day lives. We do not live in a society where it is regularly necessary for medical professionals to prioritize their treatments according to who they have the best chance of saving, as opposed to what is most likely to help the individual.

The reason we use the term “triage” for this process is because during battle, patients are divided into three categories:

- Those who are likely to live, regardless of received care.

- Those who are unlikely to live, regardless received care.

- Those who might live if immediately treated.

The third category is obviously the ugliest, and this is what physicians across America are now grappling with. It’s comparatively easy to isolate those who either clearly will or clearly won’t live. The question is, is it better to try to save 2-4 people with a machine that’s not intended to do so, thereby risking all of them, or to focus maximum survivability on a smaller group of patients?

Even if there is a right answer from a utilitarian perspective, there’s no way to know the answer before thousands of people die one way or the other:

The most dangerous idea about this epidemic is that no one will be impacted in a serious way if we reopen the economy and send everyone back to work:

- March 2: 100 cases in the United States

- March 10: ~1,000 cases in the US (994, technically, but March 11 is 1,301)

- March 18: ~10,000 cases in the US (9,197, but March 19 is 13,779)

- March 27: ~100,000 cases in the United States (96,920 as of this writing).

This is the rate of increase across the United States today. Given the incubation period, we might start to see the impact of social distancing in states that adopted it early in the next 7-10 days. But the rising caseload in other states will almost certainly offset it. We are averaging eight days per 10x increase in cases.

I don’t know how quickly the pandemic will continue to grow. Hopefully, social distancing will begin to take effect. But these are the decisions doctors are already grappling with as the pandemic spreads across the country.

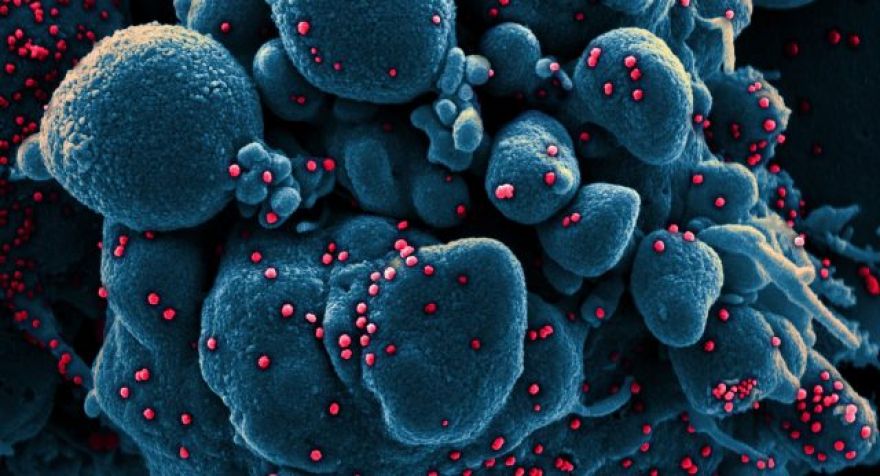

Top image credit: NIH

Now Read: